11 Oct 2018 - 12 min read

Crafting a CHI Rebuttal

Writing a CHI paper takes a long time, and waiting on your reviews can feel even longer. CHI allows authors to directly respond to reviewer’s feedback through a rebuttal process. However, unlike writing your paper, you are not given a lot of time (or characters!) to craft your CHI Rebuttal and it can be the difference between an accept or reject.

UPDATED FOR CHI2020

The review timeline changes slightly each year, but the important dates for rebuttals this year (CHI 2020) are:

- Reviews sent to authors: November 15, 2019 at 12pm (noon) PST / 3pm EST / 8pm GMT.

- Rebuttal period closes: November 22, 2019 at 22:00 ET.

This only gives you five working days to: read your reviews, swear at R2, cry a little into a wine glass, and of course write, review and submit your rebuttal. Not a lot of time to process the feedback and work out a plan of attack. Below I’ve written how I approach reviews and rebuttals in general in case it helps.

Review Terminology

First, you should become familiar with the terminology used to describe each of the reviewers. This is important because these people have different levels of responsibility:

- ACs – Associate Chairs

- 1AC – Primary AC (coordinates the review process and assigns two external reviewers)

- 2AC – Second AC (Writes a full review)

- R1 - External Reviewer

- R2 - External Reviewer

- **3AC –** Third AC (Only added if there is a big difference in scores across reviewers)

Analysing

On receiving your reviews, it can be hard to know where to start. It can be very overwhelming, especially if this is your first time receiving reviews from CHI. After you read the dreaded email containing your reviews, close your laptop and go and do something else. You aren’t going to be productive at this time, so come back to it later.

After you’ve given yourself some thinking space, it’s time to get to work on your rebuttal. The first I recommend is that you download your reviews in plain text format, as they are simply easier to read when out of the PCS system. Next, print your reviews or allow yourself some way to read them without being able to type anything. You need to give yourself time to really understand and dissect what the reviewers are saying.

First Read Through

During the first read through, don’t focus too much on individual points, your goal here is to understand where each of the reviewers stand. Who is the most positive (or the paper’s champion) and who is the most negative (the paper’s destroyer)? This is a crucial step of your rebuttal, as within a small amount of characters (last year it was only 5000) you need to give the champion more reasons to love your paper, while at the same time reduce any lingering ammo that the paper’s destroyer could equip. Your overall goal is to convince the AC’s that your paper deserves to presented and published at CHI.

Second Read Through

On the second read through, focus on individual points using highlighters. I use two colours and highlight positive and negative points raised. It can be very easy to focus on the negative things reviewers say, but you need to balance this by focusing on the positives too!

Analysis Phase

I will now begin to analyse my reviews as if I’m coding qualitative research data. If you have never done this, think of it as “tagging” extracts of text with meaningful labels (known as codes). Go through each review and ‘code’ individual points raised while also ‘coding’ each point with the reviewer’s label (this is a very important step - which I’ll explain below). I use MAXQDA, but you can also do the same thing using Excel.

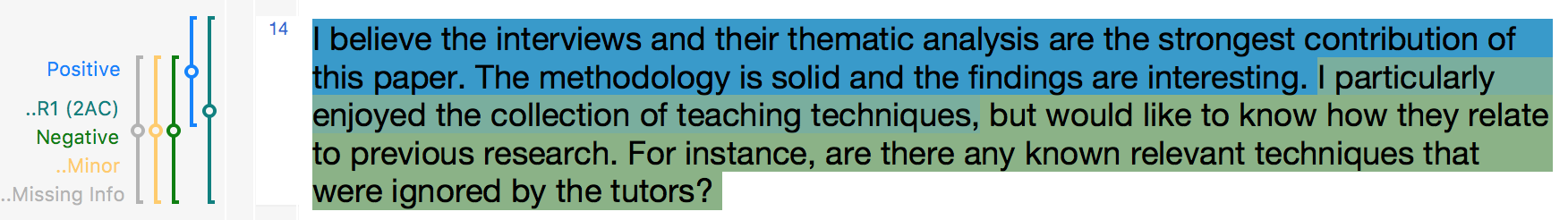

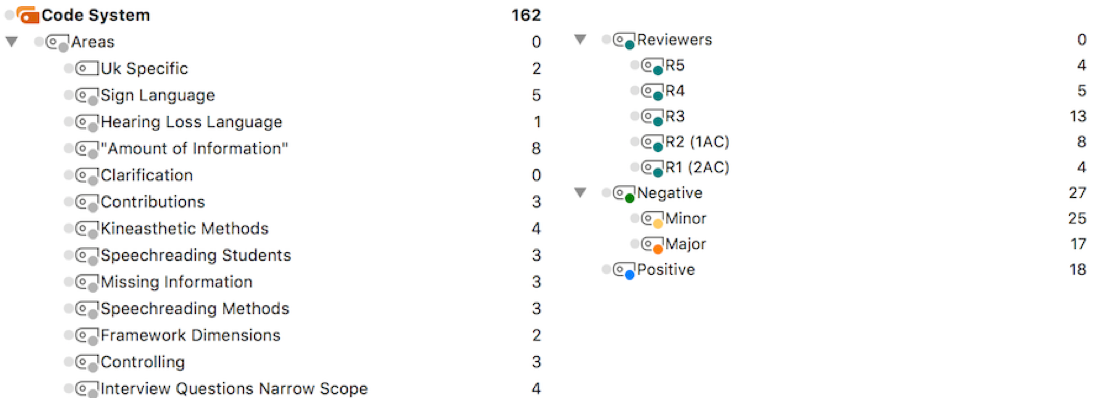

See Figure 1 for an example of two coded extracts, and Figure 2 shows my final list of codes. At the end of this phase you’ll be able to collate all extracts under the same code.

Figure 1: An example of a coded excerpt from my 2017 CHI paper reviews. The first extract is coded as “Positive”. The second extract is coded as “Negative” and is about “Missing Info”. I’ve coded it as a “Minor” point because I simply could add this in my final paper. Both extracts are coded as being written by “R1 (2AC)”.

When you have finishing coding your reviews, you’ll be able to produce what I call “collated comments”. This will be a list of similar comments by different reviewers collated under each of your codes. For instance, perhaps the 2AC and R1 were concerned about your statistical analysis; “Data Analysis” could be the code that these comments are collated under.

Figure 2: The final code system from my 2017 CHI paper reviews. You can see “Amount of Information” was the most raised point by the reviewers. This was an important point to discuss in my rebuttal, and the reviewers were right to raise it.

Once you have a set of collated comments read through them again and start to move each group of comments around the document in order of priority. For instance, if you have a confound in your study this would be of very high priority, or if something is raised by all reviewers again this would be high in priority.

At some point during this phase, you need to draw a line and say where “Major” and “Minor” points are. You can’t address every point in your rebuttal, as there is simply not enough characters. You can then take this document to your supervisor or collaborators and discuss how to respond to each of the points raised.

Responding to Points

Now you have a good understanding of what the major concerns are about your paper, draft a sentence or two against each of the points. When responding to reviewers be courteous and polite, reviewing is often a thankless task so be grateful they have taken the time to give you feedback - even if you currently despise them!

It’s important to know at this stage that you can’t promise drastic changes, the timeline for camera ready submissions is very short. In fact, reviewers are told to accept papers “as is”, because there is no way for reviewers to check that the authors did the changes they said - this responsibility falls to the 1AC but they don’t have time to check each paper thoroughly. Therefore, if you suggest too many changes this will kill your paper’s chances, as it’s clearly not ready to be published.

Always remember that a reviewer’s only knowledge of your work comes from reading the paper, so if they are confused about an aspect of your research, then the writing in your paper has misled them. However, If you do think a reviewer missed something that was in your paper, don’t outright state this, kindly direct them to this information.

For instance, perhaps R1 didn’t appreciate the way you analysed your qualitative data. However, you provided a reason or citation for this in your paper. Directly point this out to the AC’s by using the citation number number and page number where you provide justification. For instance you could say the following:

R1 requested more details on our analysis of open-ended question data. We followed Braun and Clarke, and did not conduct inter-rater coding following the justification provided in [23] (pg 4).

Each response should convince reviewers that you’ll be able to address their concerns within the revision period. You don’t need to provide the exact wording; just outline the change you will make and where. In some cases, you won’t need to make a change, instead you will need to convince reviewer’s you have done the right thing by providing evidence or justification.

An often overlooked aspect of writing a rebuttal is not outlining how you will make space within your paper for new content or changes (e.g., a new paragraph to justify an aspect of your study design). In these cases outline to reviewers where in the paper you expect to be able to reclaim space - but tread carefully, you don’t want to remove something that some reviewers think is valuable (I made this mistake before and a reviewer dropped their score post-rebuttal!).

Formatting

Formatting your rebuttal is extremely important, even though you only have a limited number of characters to play with, you still need to make it easy to read.

In particular, ensure your rebuttal allows reviewers to easily find your responses to the points they raised. Refer to reviewers by R1, R2 etc. (this is why we took the time to code the extracts with their labels!).

Use bullet points and whitespace to allow for quick scanning. Start with the major points going down towards minor issues. You don’t need to say you will fix typos and small mistakes, this is expected. Below is an example format, that has worked for me in the past:

Thanks to the reviewers for their insightful comments. We are confident that all concerns can be addressed within the revision period and believe our paper presents a valuable contribution to the CHI community.

POINT A: 1AC 2AC R1 // If reviewers missed things you can point their attention by saying (pg. 6)

POINT B: ALL Rs

POINT C: 1AC 2AC

POINT D: 1AC 2AC

POINT E: R1 R2 Thanks to R1 & R2 for pointing out that we do not discuss…

MISC // Minor Points Raised could go here

Finally, we will address all other concerns through a full edit pass, and ________________ to create additional space as needed.

Once you have finished a draft, send it to your supervisor, peers and collaborators. It can also help to send it to a neutral party (a friend, partner, family member) who isn’t a researcher, as they may pick up on an angry or dismissive tone that others miss.

Take Home Process

Ok. So I’ve covered my process in more detail than I originally intended to, but here are the main steps:

- Process the feedback.

- Analyse the points raised.

- Collate the points raised (by coding the data set).

- Prioritise the points (draw a line at major vs minor points).

-

Draft a response to each point (and get a second reader).

- Focus on the formatting (and cut to the character limit).

- Submit and know it’s now out of your hands!

Conclusion

So is it worth always writing a rebuttal? In my opinion, YES! However, it won’t necessarily save your paper. Your rebuttal will really only play a role if your paper is borderline, or your reviewers did a poor job.

In my three paper submissions to CHI, twice my rebuttal led to reviewers raising their scores. Although, the first time I wrote a rebuttal I said I would take a section out to please one reviewer and this led to another reviewer dropping their score - so it doesn’t always work out.

Regardless of the outcome, writing a rebuttal will help improve both your paper and your future research approach, so it’s well worth the effort. Good luck!

What does your process for crafting a rebuttal look like? Did I miss something? Drop a comment or tweet me @benjgorman

Some other useful posts on writing rebuttals:

SIGCHI Rebuttals Some Suggestions

How to Write an ACM SIGCHI Rebuttal

Patterns for Writing Good Rebuttals